The previous names we talked about – surname and given name – are, sadly, pretty much the only names that Chinese people have these days. You can say it’s not sad in that it’s simplified, but look at the examples of terrible names in the earlier post.

Of course, just as someone whose parents named him Havelock might just choose to go by, say, Avy (Locky?), and someone whose parents named him Socrates might hold symposia and get some deep thinking done (or drink hemlock, and yes I know a Socrates, and he’s ethnically Chinese), there are – well, were – ways of getting around such nominative messes in historical China. These are the courtesy names, and the pseudonyms.

Also, if one has gone far enough up the mortal coil before being eased off it, they would also be given names, or more accurately, posthumous titles. Which is, of course, a nice gesture – most of the time, anyway. People recognise that, if you’re highly-ranked enough, your non-existence is no reason for people to not gossip about you.

Courtesy names (字, zi4)

Courtesy names exist because, according to the 2,700-year-old Classics of Rites, it is impolite to call people by their given names. The name people get at birth are for the ones who gave or suggested it – the parents, their aunt who thought it might be nice to call them Erectile Dysfunction or Shaking All-About, those people.

This is naturally a drag once you are old enough to have plenty of friends, so traditionally most literate Chinese would, on maturity, give themselves a courtesy name. And this is why, in many texts like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, keeping track of names often becomes a nightmare by Chapter 10 – on top of figuring who’s been hacked and who’s not, many people have two or even three names by which they are addressed. Some examples from that period (184 – 280):

曹操 Cao2 Cao1, courtesy name 孟德 Meng4 De2

劉備 Liu2 Bei4, courtesy name 玄德 Xuan2 De2

諸葛亮 Zhu1 Ge3 Liang4, courtesy name 孔明 Kong3 Ming2

孫權 Sun1 Quan2, courtesy name 仲謀 Zhong4 Mou2

The name is self-given, and so you are free to call yourself what you want. General rules do tend to apply, however. For one, there is the question of birth order; quite often one of the two words would be used to denote the birth order of the person, from oldest to youngest: 伯 bo2, 仲 zhong4, 叔 shu1, 季 ji4, and sometimes 幼 you4. Indeed, even now, 伯 is used to address one’s father’s older brothers (older uncles), while 叔 is for paternal younger uncles. Another option for the oldest chlid is 孟 meng4, though I’m not sure what the derivation for that is.

So, for instance, Sun Quan’s courtesy name is 仲謀 Zhong4 Mou2, and that’s because he’s the second son in the family – his older brother Sun Ce 孫策’s courtesy name is 伯符, Bo2 Fu2.

Another general rule is that the courtesy name tends to reflect, in some way, the actual given name, often by using a related word. Cao Cao’s given name, 操 cao1, roughly translates to ‘virtue, purity’ (yeah, the irony is not lost on me); and so his courtesy name, 孟德 meng4 de2, refers both to him being the first son of his father, and to 德 or virtue.

None of these are absolute rules, of course. There are some literati who much prefer to have their names oppose rather than support each other. The great essayist and poet of the Tang Dynasty, Han Yu 韓愈 (768 – 824), has a given name 愈 yu4 which means ‘to advance‘; his courtesy name, however, is 退之 tui4 zhi1, which means ‘retreating’. I bet he was a great wit. (Judging by the essays, he wasn’t. Sorry to spoil. I might translate some later and you decide.)

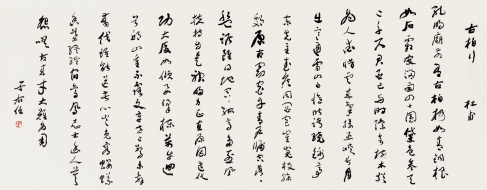

Pseudonyms (號, hao4)

So the courtesy name is there for friends, and not unlike the given name there is also some element of aspiration in it – except, perhaps, from a more adult, mature perspective. But aspiration is so mainstream, so what you want if you actually want a unique name that really says who you are, you get a pseudonym.

Pseudonyms tend, in Chinese culture, to be the preserve of poets and writers, and are often associated with geographical features, or some of their particularly witty sayings and beliefs. Many of the geographical feature pseudonyms are in turn derived from the places where they live – at least, where they live when they were poor and lived in interesting places, or got exiled from court into interesting places. You wouldn’t call yourself the Resident Scholar of Canary Wharf, and nor do the Chinese.

Indeed, there are some historical writers who are more commonly referred to by their pseudonyms; one example is the great Song Dynasty (961 – 1279) poet, painter, statesman etc. Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037 – 1101), pseudonym 東坡居士 dong1 po1, literally Resident Scholar of the East Slope, who in Chinese is often called Su Dongpo 蘇東坡, East Slope Su.

Some examples of pseudonyms are below:

諸葛亮 Zhu1 gee Liang4 (again), pseudonym 臥龍 Wo4 Long2 ‘Reclining Dragon’, named after Reclining Dragon Ridge where he lived

李白 Li3 Bai2, pseudonym 青蓮居士 Qing1 lian2 ju1 shi4, literally ‘Resident Scholar of the Blue-green Lotus’

Posthumous Names (謚號, shi4 hao4)

We Chinese people are seriously into history (it’s not just me, I swear!), and also quite bitchy (also not just me), and so we have this ancient tradition of posthumous names. We’re never going to hear our own, so that’s not much to worry about, but of the different sorts of names, this is perhaps the most formalised one, with the most rules. If given and courtesy names are aspirational, and pseudonyms are so hipster and ‘just the way I am’, then the posthumous name is a committee sitting over your coffin evaluating your life performance.

Nice image, eh?

Posthumous names are reserved for emperors and officials, and especially for emperors they are the main form of address – the emperor’s personal name is far too sacrosanct to be mentioned, and that is why we have titles like Emperor Wu of Han (156 BC – 87 BC, r. 141 BC – 87 BC), Emperor Wen of Wei (187 – 226, r. 220 – 226) and so on. In their cases, 武 Wu3 means ‘martial’, and 文 Wen2 means ‘civil’; some other common and complimentary posthumous titles include 明 Ming2 ‘bright, discerning’, 景 Jing3 ‘decisive, admirable’ and 穆 Mu4 ‘amicable, harmonious’.

There are derogatory posthumous names, though these are much rarer; Emperor Ling of Han (156 – 189, r. 168 – 189) has the title 靈 Ling2, which means ‘inattentive, lazy’.

For officials, posthumous titles are often given by the imperial court on their death, in order to commemorate their public service. This, in turn, means it is often possible to tell which writers and scholars have been high-ranking officials, and which ones either never joined imperial service (not very common) or got exiled due to political struggles at court (very common).

The writers who do manage to get posthumous names tend to have their collected writings published under that posthumous name – another literary tradition in China. Partly because of this tradition, there are also writers who are often known by their posthumous names; perhaps the most famous is the Song Dynasty minister and scholar Fan Zhongyan 范仲淹 (989 – 1052), whose posthumous title was Wenzheng 文正 ‘civil and righteous’; he is often known as Fan Wenzheng Gong 范文正公, ‘Lord Fan, civil and righteous’.

So that’s about it (for now) for names. I’m not going to go into too many examples, partly because I will be going into a lot of those writers – in fact, writing this is making me recall all these other writers I need to post about! Well, no end of material for the blog then…