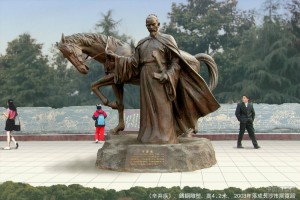

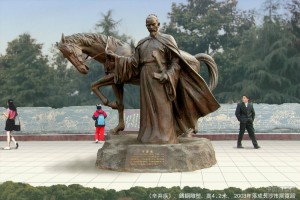

Xin Qiji, looking appropriately brooding and heroic

For some reason the idea of poetry is seen as being ‘unmanly’ these days – something I have never understood. The poetic spirit has risen out of all sorts of places, and ever since history there has been plenty of war poems – the earliest great poems, like the Iliad or the Mahabharata, were all about killing people in very large numbers.

So it is too with China. Today’s poet, 辛弃疾 Xin Qiji (1140 − 1207), is as bad-ass as Chinese poets come. Born in the waning years of the Northern Song Dynasty, when it came under repeated attacks from the rival Jin Dynasty and eventually retreated south (as so many Chinese dynasties do), Xin was an ardent nationalist and a fighter too. It was something that ran in the family; he was named Qiji, which literally means ‘to forsake illness’, to reflect the name of a great general from the Han Dynasty, 霍去病 Huo Qubing (140 BC – 117 BC); Qubing also means ‘to ward off illness’.

A famous wartime exploit of his was when one of his former comrades in the struggle against the Jin Dynasty, a man named Zhang Anguo, switched his allegiance, murdered a Song general and went to the Jin camp with the general’s head. Enraged by this, Xin led a hand-picked group of 50 horsemen, charged into the Jin camp at night, and dragged Zhang Anguo out to be delivered for execution. Because he’s a cultured man, presumably, and due process is the way!

Things did not go so well for him, though, with his own authorities; the pro-peace sentiments in the Song court meant that Xin was repeatedly sidelined, which in the end was not good for his health and mood. It’s turned out quite well for Chinese literature, though, as frustration tends to; much of Xin’s best works, like the following poem, came from his later years.

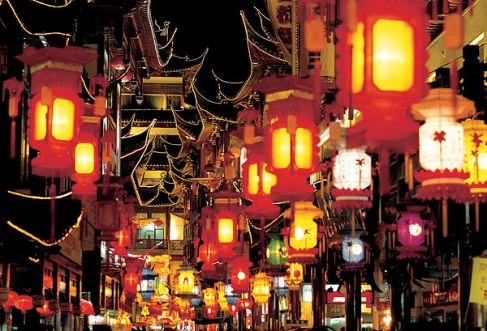

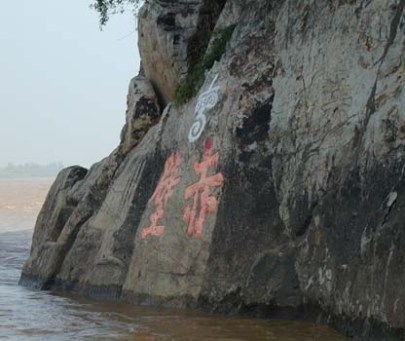

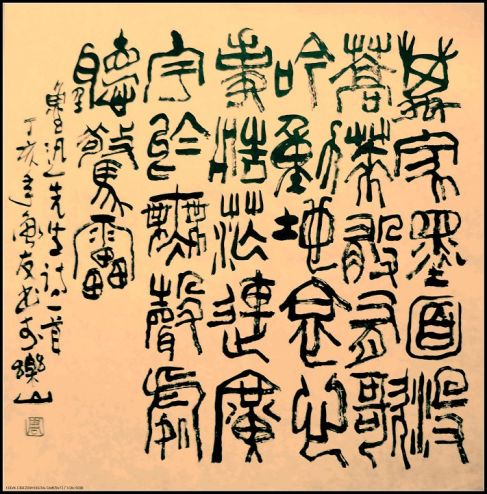

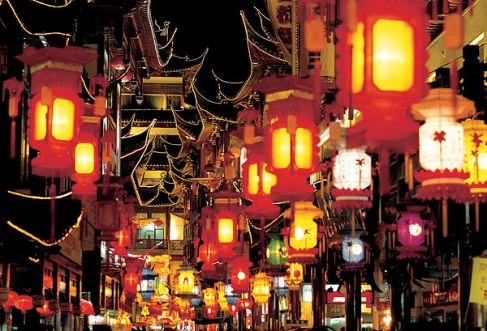

There is a certain ambiguity in this poem; on one hand, it could be a romantic poem about finding a loved one during the Lantern Festival, when young men and women were allowed to mingle and admire lanterns. On the other hand, given Xin’s political frustrations, it could also be about the strange gilded age around him in the southern capital at Lin’an (modern day Hangzhou) – the Southern Song Dynasty, after all, was immensely rich, wealthy and cultured, and yet always teetering at the edge of being destroyed.

Fun fact about this poem – the Chinese search engine and portal Baidu, which literally means ‘a hundred times’, comes from a line in this poem. Which makes sense, as you will find out.

Continue reading →